Online Human Rights? Towards a Cosmopolitan Framework for Internet Policymaking in the Digital Era1

Rodrigo Muñoz-González

R.A.Munoz-Gonzalez@lse.ac.uk

London School of Economics and Political Science (Reino Unido)

Recibido: 29 de junio de 2018

Aceptado: 23 de julio de 2018

Publicado: 28 de noviembre de 2018

Para citar este artículo

Muñoz-González, R. (2018). ¿Derechos humanos en línea? Hacia un marco cosmopolita para la formulación de normativas en la Internet de la era digital. Correspondencias & Análisis, (8), 13-31. https://doi.org/10.24265/cian.2018.n8.01

Abstract

This article discusses an important challenge for Internet governance: the difficulties entailed in articulating the multiplicity of scenarios and contexts that shape it. A “multistakeholder” approach has been posited often as the most suitable path to build Internet governance. However, materializing this approach is difficult because of the possible actors and situations found on the Web. Instead, and building on the notion of cosmopolitanism (Boczkowski & Siles, 2014), this article proposes an alternative framework for studying Internet policymaking. It applies this framework to the Digital Privacy and Security Statement advanced by the Global Commission on Internet Governance in order to show how it can help further our understanding of Human Rights in the digital era. It argues that cosmopolitanism can offer a method that helps to transform a complex network of interactions into a map characterized by different objectives and relations in order to generate more dialectic Internet policies.

Keywords: Internet, Policymaking, Governance, Human rights, Digital media.

Resumen

Este artículo aborda un importante reto para la gobernanza de la Internet: las dificultades que conlleva la articulación de la multiplicidad de escenarios y contextos que la conforman. El enfoque de “múltiples stakeholders” surge como el camino más adecuado para construir la gobernanza de la Internet. Sin embargo, la materialización de este enfoque resulta difícil, debido a los posibles actores y situaciones encontradas en la web. Este artículo, basándose en la noción de cosmopolitismo de Boczkowski & Siles (2014), propone un marco alternativo para estudiar la formulación de políticas en la Internet, aplicándolo en la Declaración de Privacidad y Seguridad Digital Avanzada por la Comisión Mundial sobre Gobernanza de la Internet, con la finalidad de mostrar cómo puede ayudar a fomentar nuestra comprensión de los derechos humanos en la era digital. Se argumenta que el cosmopolitismo puede ofrecer un método que ayude a transformar una compleja red de interacciones en un mapa caracterizado por diferentes objetivos y relaciones, a fin de generar políticas de Internet más dialécticas.

Palabras clave: Internet, Normativa, Gobernanza, Derechos humanos, Medios digitales.

1. Introduction

Internet, as technology and medium, poses an important challenge: within its possibilities of action, there are many scenarios and contexts that hinder its governance from a traditional standpoint (Waz & Weiser, 2013; Weber, 2009). Therefore, a set of Human Rights focused on the “new” media, the so-called “Fourth Generation”, becomes a task, with almost labyrinthic features, necessary to resolve and to consider in every debate centered on the Internet (Dutton & Peltu, 2007).

Any policy creation regards the deft study of multiple perspectives and experiences, and a satisfactory prevision of its possible consequences. This approach becomes crucial in the contemporary dynamic in which the time-space boundaries are getting dimmer every day; as Castells (2008) underlines, “the new political system in a globalized world emerges from the processes of the formation of a global civil society and a global network state that supersedes and integrates the preexisting nation-states without dissolving them into a global government” (p. 90). Media rights, in this sense, pose a hard dilemma: from a global to a local coverage, Media is embedded in a dynamic in which production and consumption play a role depending on a specific context.

Researchers have often considered a “multi-stakeholder” approach as the founding principle for Internet governance (Drake, 2004; Hintz & Milan, 2009). Considering all the interests besieging the Internet, it takes multiple perspectives into account in order to establish a regulation or policy. Nevertheless, it fails in addressing a concrete form of procedure: as a principle, it does not give clear pathways to edify concrete actions (Hamelink, 2012).

The cosmopolitan approach, advanced by Boczkowski and Siles (2014) to understand the development of media technologies, provides a model for integrating the study of production, content, consumption, and materiality in a communicative process. In this sense, this optic may be used as a potential framework for understanding the multiple forces that interact on and through the Internet. This model provides concrete guidelines to build Internet policies that take into account all the agents and networks of influences that interact around a certain issue. From a human rights perspective, it helps to identify more clearly the map of actors and interests that embrace the arousal, defense, or violation of several rights.

This article draws on this cosmopolitanism approach to propose a framework for organizing the multiple forces that surrounds the Internet. Unlike with the “multi-stakehold” approach (which emphasizes how various actors engage in the search of solutions without being able to deepen into the tracks these actors follow), this essay focuses on the Internet governance system involved in the protection of Human Rights as a whole.

The Digital Privacy and Security Statement made by the Global Commission on Internet Governance (2015) was scrutinized with a cosmopolitan focus in order to prove its functionality as analytical tool and to promote the understanding of the human rights within the Internet. In this case, the privacy and security issues that embodied the “online Human Rights” face a significant challenge because of all the agencies involved, from States and Corporations to ordinary citizens, proving the need for concise multi-stakeholder solutions.

In what follows, the relationship between human rights and Internet is discussed to observe the hard dilemmas that appear within it and different viewpoints that have emerged in order to addressed it. Then, the association amid Internet governance and human rights is scrutinized, studying Multi-stakeholderism as a perspective that tries to integrate all the actors affected by a possible future policy. Next, cosmopolitanism is explained as way to give form to the Multi-stakeholder optic, being applied in the analysis of the Digital Privacy and Security Statement. The final section of this essay summarizes the analytic advantages of the selected framework for understanding the complexities of Internet governance and for achieving a more dialogic and democratic Internet experience.

Globalization demands a thorough consideration of Human Rights, from their principles to their application (De Semet et al., 2015). This essay problematizes how Internet policymaking can secure its defense.

2. Online Human Rights: Challenges with a Dot Com Domain

The discussion regarding Human Rights on the Internet has many edges, recreating multiple viewpoints and possibilities (Horner, 2011). The main task is related to the universality intended to be achieved in the field, and the peculiarities that are generated everyday on the Internet. Furthermore, the medium is used around the globe, setting important differences in every context of access: indeed, there are palpable shifts in developed or developing countries (Hamelink, 2011).

For Martín-Barbero (2012), there is a divorce between the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the actual “Information Societies”; the modifications inserted by the new technologies, then, need to be reinterpreted to satisfy the new and future conditions. As he considers, “this declaration does not make explicit the constitutive relationship between the new rights that society’s computerization implies and the human rights known before” (2012, p. 158). Martín-Barbero’s assertion reveals distinct areas of the Internet in which Human Rights must be (re)considered, (re)elaborated, and taken in serious consideration.

If Internet can be proposed as a Human Right (Lim & Sexton, 2011), the access/use implications of Internet become crucial (Ziccardi, 2013); as Leo Marx (1997) underlines, a technology is a concept with social and cultural outlines, but with a material basis that is found in many artefacts and appliances. For Lucchi (2014), the conception of access to the Internet may be described in three ways: “a) access to network infrastructure, b) access at the transport layer and services, and c) access to digital content and applications” (p. 820). Regarding the attempt of UNESCO (2013) to promote an Internet Universality, the materiality of the medium must be recognized in order to earn this goal. In this manner, “access to the Internet should be protected as strongly as the various forms of participation and expression that it allows” (Lucchi, 2014, p. 836).

Although a discussion regarding the legal state of the Internet is needed, its material basis must be analysed in order to comprehend the spectrum that it carries. The medium is considered global, but “globality”, as category, implies power relations that cross many systems; as Ampuja (2011) remembers, the social and economic fields point out specific material circumstances and situations. Sometimes, distinct leaderships regarding the Internet are uttered in privileged backgrounds, obviating that a certain “principle”, for instance, depends on multiple factors that changes from country to country. The human rights discussion must not fall in dangerous generalizations: there are large differences between developed and developing regions. The “universal reach” of a policy should contemplate that its application will go through several variations depending on factual conditions. Procuring Internet access in any zone means to study its cultural and concrete context. In this sense, different initiatives lack the proposition of tangible actions for particular landscapes; the access issue has fallen into a vague terrain and has forgotten that reality is held within invisible and visible structures (Giddens, 1986; Morley, 1992; Sterne, 2014a).

The technological infrastructure of Internet is related, also, to its content. Hence, many efforts have been held to safeguard the freedom of expression on the cyberspace (Puddephatt, 2011). In many moments, issues as security, surveillance and “Net Neutrality” have placed, at the centre of the discussion, the user’s freedom of creating and consuming Internet content, corroborating the significance of defending the human rights on the Internet (Bauman et al., 2014; Horner, 2011; Kovacs & Hawtin, 2013). But, for García Canclini (2012), another remaining task in this area is the understanding of the inequalities that take shape on the Internet, meaning that there still exists a cultural hegemony that favours specific values and structures. The works of Webster and colleagues (2012, 2014), illustrates that, even though the Internet has opened a terrain of almost infinite information, the audience behaviour is moving toward mainstream outlets of content; thus, the evidence does not support the hypothesis of fragmentation on the Internet, but of concentration within certain sites and services. This concentration operates in American-influenced modes of media production, highlighting a still prominent cultural dominance.

Despite this situation, Internet content can serve as a path to promote the defence of human rights. According to Echeberría (2012), along the Internet, the user’s dignity must be respected, but, moreover, the medium “can be a catalyst for the exercise of Human Rights” (p. 50). The Internet has been an opportunity to denounce abuses of power, to mobilize social movements, to claim directly for the respect of civilian rights (Ziccardi, 2013). The protests during the Arab spring uprisings are an example of how the Internet might be the home of dissident voices, and of how, as technology, may serve as a tool for citizen journalism (Hänska-Hay & Shapour, 2013). Nevertheless, as stated above, the materiality of a context withholds the usage of the Internet, in this case, as a freedom sponsor; a political environment is attached to a material kernel.

For Hamelink (2012), the most prominent challenge regarding the relation between human rights and Internet is the creation of actions with a degree of effectiveness: “We need to realize that the incredibly difficult task ahead is to give genuinely concrete meaning to normative standards that are often useless abstractions in real-life situations” (p. 56). This effort can be completed through the implementation of policymaking processes that distinguish the Internet’s substance and effects. At the end, the best way of protecting human rights is to propel initiatives with appreciable results.

3. Internet Governance: A Never-Ending Effort

To analyse the Internet is to analyse the global media landscape. The new technologies have created different experiences of many types, obliging efforts of study them in order to create policies that embrace this new situation. Perhaps, the most common tendency is to understand a specific issue when this affects something or someone, as a “firefighting” effort (Mayer-Schönberger & Ziewitz, 2007).

For Raboy & Padovani (2010, pp. 162-163), the multiplicity of interdependent and autonomous actors involved, with different degrees of influence and power, in policyoriented processes have become the infrastructures for any media regulation. Regarding the Internet, the attempts of establishing a “jurisdiction” are complex due to all the forces involved in the production and use of the medium. In this sense, Braman (2004, p. 175) suggests that the domain of media policy in the twenty-first century is connected to social life and economy by technology, with Internet being its gravitational centre, emphasizing the need of adopting an approach that must map the empirical reality, include all matters of concern, rest on theoretical foundations, be methodologically operationalizable, and be translatable in new policy principles.

MacLean (2005, p. 32) proposes that Internet governance is a “governance network of governance networks”, distinguishing the meeting of public initiatives, the private sector, civil society at many levels, and other groups, each one with a repertoire of different goals and protocols of communication. Thereby, different endeavours have been made to provide a set of values for Internet governance. The two editions of the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), and other organizational actions, have led to discuss principles for an effective Internet management (Hintz & Milan, 2009; Krummer, 2005; Raboy, 2004; Weber, 2009). Nonetheless, the integral path, which tries to coordinate all the different points of view that surface the Internet, set as a basis for the matter, have not found a concrete form (Drake, 2004; Puddephatt, 2011).

Prior to the organized efforts on structuring an ethos for the Internet, Vedel (2005) had found four main approaches of governance that had been taking shape loosely along the Internet according to certain contexts. The first, community governance, was based on “spontaneous solidarity and interdependence of interests between stakeholders who share a set of values and identify with similar norms” (2005, p. 63), meaning the absence, and need, of formalized arbitration mechanisms. Market governance, the second one, consisted in the dispersed competition between autonomous actors, whose interest could be independent of one another, in a race for individual advantage, being the price system the mean of arbitration (2005, p. 64). Hierarchical or State regulation proposed a central authority that determines objectives and goals, organizing a framework for its application on the Internet; this kind of government was associated, by its nature of action, as a “state or national regulation, or else interstate or international where it involves agreements between several governments” (2005, p. 64-65). Finally, associative regulation signalized agreements and contracts, entered by voluntary participants based on mutual relations, or relations with third parties.

These four perspectives had problems and faults but worked as a “kick-start” for the formulation of a more comprehensive approach (Dutton & Peltu, 2007; Kurbalija & MacLean, 2007; Vedel, 2005; Waz & Weiser, 2013). The discussions exposed in this section target a necessity, first, of acknowledging that Internet is a medium whose essence is carried by the users, and, second, of accepting the polyphonic ontology of the Internet; that is, to notice that there are groups with different objectives and aspirations.

In light of these observations, several researchers have worked on approaches that take into account all the viewpoints that could be found on the Internet, or at least to be aware of them. As Dutton (2005) notes, these approaches must understand the “dynamic interplay of technical, social and policy choices shaping the development of a technology, like the Internet, or a structure of governance, such as Internet governance” (p. 9).

The multi-stakeholder optic has been formulated as the most suitable path to build Internet governance, considering the vast quantity of interests portrayed by governments, the private sector, specialized groups, the civil society, and other kinds of organizations (Hintz & Milan, 2009). From a general outlook, this approach seeks to recognize the interest and positions of different stakeholders regarding a specific issue, within a context, in order to formulate an inclusive policy or regulation (Vallejo & Hauselmann, 2004). Regarding the Internet, this perspective highlights the importance of considering multiple purposes at the time of forging a stipulation related to its governance.

In fact, many initiatives and organizations related to Internet governance have utilized multistakeholderism as a way to build up their goals (Drake, 2004; Hintz & Milan, 2009; Lucchi, 2014). As Waz & Weiser (2013) argue, these processes have many advantages because they “can address Internet-related issues in a manner that is, in many or most cases, more efficient, more effective, more legitimate, and more global than the effort of governments (or even international governmental bodies) while addressing legitimate governmental concerns” (p. 346).

The model enables a dialogic reading of the different tensions and expectations among questions, controversies and concerns that arise along the Internet. In addition, its issue-andcontext driven nature enables the consideration and study of the Internet as a “network of networks”, meaning that every characteristic of the medium/technology is autonomous, in a first level, but part of a complex system, at a larger one. Not for nothing, UNESCO (2013) poses the multi-stakeholder participation among its four universal norms of being for the Internet2 . The main challenge lays in securing and maintaining, indeed, an identification of the different agents and a true balance between their networks of influence.

Multi-stakeholderism allows recognizing both the user, as an individual, and the collective in which he or she is embedded. This optic proposes the Internet as a space of human rights: the consideration and study of the different actors’ goals within Internet have implied the acceptance of the user as a political person. The Internet becomes a place no different of any other media experience, it must move in a frame that fulfils the Universal Declaration. As Dutton & Peltu (2007) emphasize multi-stakeholderism is the cornerstone that shall be present in every intention of Internet Governance.

Nonetheless, despite its advantages, this approach fails to provide a clear procedure of action. In addition to its theoretical principles (Dutton, 2005; Kurbalija & MacLean, 2007; Waz & Weiser, 2013), this model should offer modes of transforming the abstract into concrete procedures. Given its centrality on Internet policymaking efforts, frameworks like this one should be able to provide such practical procedures. In what follows, it is argued that the “cosmopolitan” approach provides a solution to this situation.

5. Cosmopolitanism: Proposing a Framework for Internet Policymaking

For Hamelink (2012), the contemporary world has brought an era of cosmopolitanism3, understood as socio-historic context that demands both autonomy and reciprocity. Thus, there is a substantial difference between the past conception of human rights and a new one. In his words,

The conventional discourse has –despite the formal pretence of universalism– no strong interest in the cosmopolitan ideals of communal responsibility and collective welfare. Conversely, cosmopolitan human rights discourse stresses the need to accept reciprocal obligations among the members of a society (Hamelink, 2012, p. 57).

This perspective equals the main arguments of Beck (2000, 2002, 2009), for whom the political order of the world has shifted toward a fragmented condition, needing a vision in which alternative ways of life and rationalities are included. Hereby, a cosmopolitan perspective “puts the negotiation of contradictory cultural experiences into the centre of activities: in the political, the economic, the scientific and the social” (Beck, 2002, p. 18).

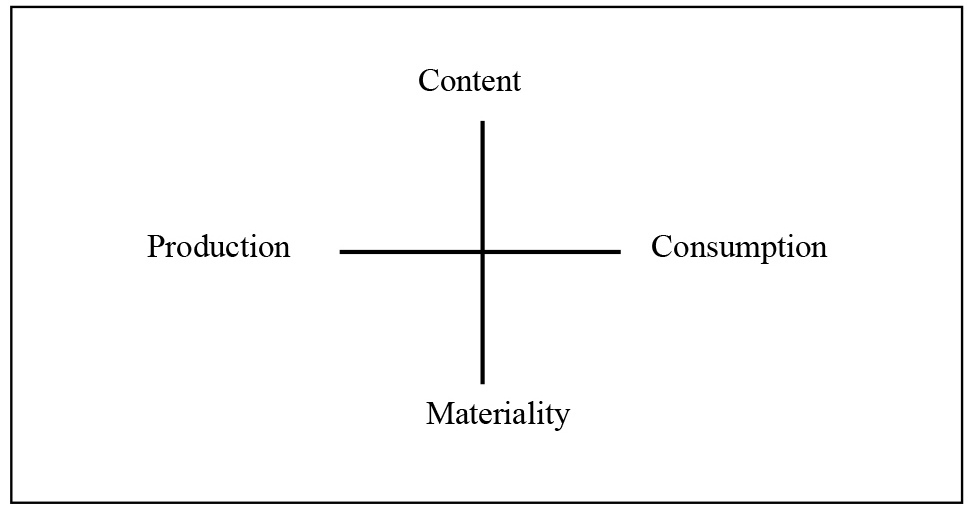

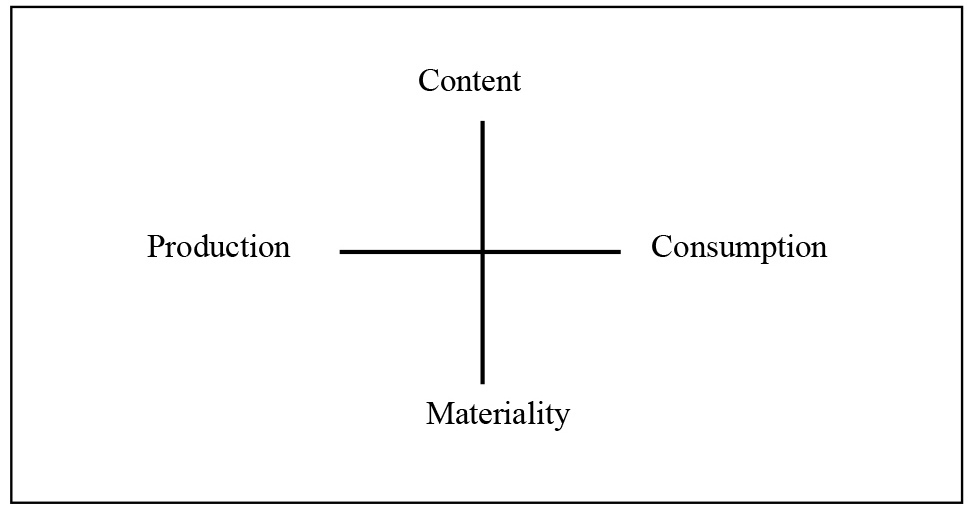

Drawing on this body of work, Boczkowski & Siles (2014) apply the notion of cosmopolitanism to the study of media and technology. These authors posit that one way of mapping the study of media technologies such as the Internet is by organizing the research along two main domains of inquiry: a) the production or consumption of media technologies and b) the materiality or the symbolic aspects of content (see Figure 1). Boczkowski & Siles (2014) contend that a renewed understanding of the social and cultural significance of media technologies in people’s lives can only occur if research is conducted at the intersection of these two axes; hence the “cosmopolitan” label. They thus argue for integrating the study of production, consumption, content, and materiality in the analysis of the media technologies.

Figure 1: Cosmopolitan framework

Source: Boczkowski & Siles (2014, p. 62)

Although it was originally developed to bring together disciplinary fields such as Science and Technology Studies (STS) and Media and Communications Research, this framework can be used in the study of Internet policymaking because it allows the operationalization of multi-stakeholderism in more concrete ways. Considering multi-stakerholderism as an ideal for Internet Governance, and from a human rights standpoint, this approach to cosmopolitanism can serve as a method that helps to transform a complex network of interactions into a map characterized by different objectives and relations in order to generate a more dialectic Internet policy.

Moreover, this framework considers the materiality of the process of communication, pointing out the entire technological basis from which the Internet functions. For instance, as Sterne (2006, 2014b) has demonstrated, a format, being a material form, can play an important role in the appropriation process of both media and technology. Hence, this approach would consider the materiality of Internet as a point of view from which understand human rights in the digital era, a necessity pointed out in past sections.

Cosmopolitanism is a path to understand the different kinds of agencies that are present in all the issues and contexts embedded on the Internet. As Dutton (2005) emphasizes:

It is by decomposing or unpacking this complex ecology of games that policy-makers and activists can focus on the objectives, rules and strategies of specific games that drive particular players, while also recognizing that each game is being played within a much larger system of action in which the play and outcomes of any one game can reshape the play, and thereby the outcomes, of other separate interdependent games (p. 10).

In order to prove the benefits of cosmopolitanism as conceptual tool, its four quadrants (production/content, content/consumption, materiality/consumption, and production/materiality) were located within the Digital Privacy and Security Statement made by the Global Commission on Internet Governance (2015). By discussing this case, it is intended to show how this model can help to further our understanding of human rights in the digital age.

6. Applying the Cosmopolitan Framework

The Global Commission on Internet Governance (2015) issued an statement titled Toward a Social Compact for Digital Privacy and Security Statement in which several suggestions regarding the Internet’s state of affairs are highlighted; therefore, a call it is made for biding effective security, prosperous business models and human rights on the Internet, considering that “all interests must recognize and act on their responsibility for security and privacy on the Internet in collaboration with all others, or no one is successful” (2015, p. 13).

Furthermore, and related to privacy and security matters, the statement signalizes the necessity of a “new normative framework, which accounts for the dynamic interplay between national security interests and the needs of law enforcement, while preserving the economic and social value of the Internet, is an important first step to achieving long-term digital trust” (2015, p. 15). Thus, cosmopolitanism is used to scrutinize the main concerns addressed by the The Global Commission on Internet Governance (2015) in the proposal in order to prove its value for Internet governance at recognizing the agencies implied in specific contexts.

6.1. Production/Content

Following the proposal by Boczkowski & Siles (2014), this quadrant explores the relations, and mediations, between the actors with the capacity of generating communicative products and the substance and expression of that content. Under this optic, the values and belief systems impressed in media constructs are studied to set the degrees in which a product fulfils its goals in relation with several elements of the final result. Regarding the Internet, this part of the framework poses its attention on the intentions behind the messages transmitted, and used, along multiple sites and social media, for instance.

The Global Commission on Internet Governance (2015) warns about possible threats that can be found in the quasi-infinite corners of cyberspace. In this sense, the organization identifies groups with terrorist or extremist ideologies that are growing quickly online, harming, at the far end, the defence of human rights. The medium, thus, has helped to spread meanings that could put in danger certain minorities. On the other hand, there have been efforts to propagate an awareness concerning the importance of security on the Internet. After Edward Snowden’s revelations (Bauman et al., 2014), the civil society has grown, also, an important attention to the subject of surveillance, obliging mutual agreements between governments, citizens, the market, and technology stakeholders Global Commission on Internet Governance, 2015, p. 8).

Thereby, the intentions behind proposing any form of Internet governance can be understood within this quadrant. Internet policies are based on notions and concepts that mark an ideology related to the role and function of Internet in society. Even though, the document in study poses multi-stakeholderism as the most popular model for online regulation, or cooperation (Global Commission on Internet Governance, 2015, p. 14), more integral perspectives can be found (Kovacs & Hawtin, 2013).

Cosmopolitanism allows the detection of the objectives behind the production of a specific content, showing the social and economic dynamics that they support. Also, the identity of the agents that generate a product is underlined, providing a clear and transparent recognition of the actors involved in a certain issue. In comparison with the multi-stakeholder lens, cosmopolitanism bridges the relationship between actors and the texts produced; in this case, forms of regulation. It improves the recognition of who wants to perform an action regarding the Internet; moreover, in a governance matter, it allows to establish in a more precise way the persons or groups that will be involved or affected with the issue of any policy: it clears the path to understand the character of the aimed political objective.

6.2. Content/Consumption

This part of the framework is responsible for the common ground attributed to audience studies, stipulating the impact of certain contents on the viewers and users, and questioning the degree of interpretation and appropriation held during the process (Boczkowski & Siles 2014). In relation to the inquiry over Internet, the quadrant has the potential of defraying, in a more specific way, the implications of the Internet usage, exposing tendencies and shifts in consumption behaviour.The statement in study shows that one of the main preoccupations regarding the Internet refers to the manipulation of personal data by websites or third parties (Global Commission on Internet Governance, 2015, p. 7). The medium, hereby, gathers a new practice of consumption: in the interaction performed between users and online content, there is an important share of data and information. A problem arises when several business approaches pursue the handling of knowledge based on the user’s backgrounds or attitudes without noticing the intention or action.

Notwithstanding the dangers entailed in this relationship, users are active agents that can counteract the flow of any kind of data along the Internet. Even, they have the possibility of changing certain aspects of the Internet, either in social media or certain platforms. The discussion of this situation on multiple places of the Internet becomes a sign of consciousness toward the issue. As Siles (2013) argues, using the case of Twitter, there are tensions between the users of a platform and the infrastructure of the platform itself, producing changes not only at an operational level but also at a textual one. Thus, Internet displays an interaction between the technology that supports it and the users, and producers, that stimulate its vigour.

The Global Commission on Internet Governance (2015) acknowledges the core of the quadrant when it aims the importance of creating more concerned Internet users that could respond to any feasible threat. The defence and consecration of human rights must pass, as well, for the involvement of the users at the moment of accessing the Internet.

A cosmopolitan approach to Internet governance may improve multi-stakeholderism by signalling the prominent role of the user. In this sense, it suggests the different types of users, and their particularities, that can be found, a variable that might guarantee the efficacy of a certain regulation. In other words, cosmopolitanism sets the ground for the analysis of the heterogeneity of actors that mould the Internet; it is a vehicle for the thorough consideration of sectors that are not powerful in terms of production.

Until now, cosmopolitanism has helped to deepen the implications of multi-stakeholderism. Next, it will be argued that the proposed approach is an effective tool to weigh a crucial dimension of the Internet: its materiality. This is a feature that differentiates cosmopolitanism from multi-stakeholderism, proving the value it can contribute to Internet governance.

6.3. Materiality/Consumption

As noted in past sections, one of the greatest challenges regarding the Internet as a cultural phenomenon is the capacity of access, pointing out the necessary means, or technologies, to navigate it. The statement in study forgets, in a general level, the materiality of the process, i.e. all the conditions needed for a user to enjoy the advantages of the medium.

Sterne (2014b) proposes that materiality is not always visible; in this case, Internet is not only formed by artefacts as computers, but also by all the “invisible” parts that constitute the devices such as microchips. The access relation to consumption is not as easy as suggesting that every citizen shall have the possibility to acquire functional equipment; there are features, as software, connection speed, or formats, that switches the whole experience as such.

From a human rights perspective, the discussion on Internet Universalism (UNESCO, 2013) is futile if access conditions are not noticed. Although it has been proven that the medium has great potential for the promotion of human dignity (Echeberría, 2012; Horner, 2011; Lucchi, 2014), it is an obligation to grasp the “situation” from which many users have their Internet experiences. And that is one of the main tests in the proposition of an “online” policy: Internet exposes the same founding principles everywhere, but it does not always function equally, it depends on the context.

Continuing with the main ideas of the Global Commission on Internet Governance (2015), the matter of privacy and security needs to fulfil a glance to the material state of the users in order to develop more comprehensive policies. Constant innovations, in content and technology, changes the Internet landscape, doing it with the user’s behaviour as well. Likewise, “consumption is also shaped by the social system or context in which the adoption process takes place and the communication mediums used to make the innovation known” (Boczkowski & Siles, 2014, p. 61). Hence, a vision that contains the potential features and artefacts available for the users become fertile to understand how privacy and security are seen on the “Cyber-Agenda” of the new public sphere (Castells, 2008). The consideration of users in an Internet policy means, at the same time with other factors, to recognize their material conditions.

As Ampuja (2011) clearly states, sometimes a certain phenomenon is considered as a cause of itself, obliterating the materiality in which it operates. Cosmopolitanism permits to pose this question on the Internet. Communications and media studies have tended to forget the material processes of everyday life; after all, the social and cultural experience of humankind needs a concrete form for functioning, it is based in material stimulus. Sterne (2014a) indicates that a conscience toward the assertion of materiality in social sciences and humanities has risen. This, evidently, becomes an opportunity to study it, to recognize it, within the Internet. In this sense, cosmopolitanism goes further than multi-stakeholderism in the consideration of the material conditions for Internet governance.

For Sterne (2006), a decisive feature of Internet materiality consists in the formats. In his view, these models of form and compression of archives have permitted the openness and elasticity of the medium, being the mp3 the quintessential example; nonetheless, the nature of the Internet have also swelled their propagation, becoming an almost symbiotic relation between media and certain formats. Moreover, a format can be linked with the production level. This relationship is addressed as follows.

6.4. Production/Materiality

As remarked before, the Global Commission on Internet Governance (2015, p. 11) obviates the materiality anchored on the Internet at the time of enumerating the core elements of a social compact for a digital society. The production of the technology for Internet infrastructure carries a problematic centre: how are the processes that establish the many material basis of the Internet? Consequently, it is obvious that some kind of hegemony is unfold along the medium, or rather an accumulation of power of decision held by few groups and unknown to the majority (Hintz & Milan, 2009; Waz & Weiser, 2013). Following the considerations made for the last quadrant, and in order to illustrate this point, the creation of a format goes through several stages and organizations that set its principles of operation (Sterne, 2006, 2014b), signalizing a concentration of arrangements; nevertheless, sometimes, and specially in this case, it is not easy to postulate an open and democratic process because it will cost time and resources to achieve it.

From a human rights standpoint, the production/materiality liaison poses the question of arbitrary or closed impositions concerning the technology used for the Internet. In this sense, “Actor-Network Theory” has emphasized the prominence of relations held, in a historic moment, between human and non-human agents in the creation or acceptance of certain gadgets or devices (Latour, 2005). What concerns the subject of this analysis is the role that certain relations play in establishing networks of influence, favouring specific actors over others (Law, 2009). Hence, there is a considerable separation, in terms of power, amid “Internet producers” and users: not everyone has the tools and skills to develop technology for the Internet.

The support, proposed by the Global Commission on Internet Governance (2015), of multistakeholder organizations sketches a focus of what could be this quadrant. Undeniably, a solution for “Internet inequality”, being the capacity of producing content and technology, is found in initiatives that moor different viewpoints and ideologies with the intention of generating a lush dialogue. Sometimes advocacy does not mean true representation.

In terms of materiality, cosmopolitanism not only warns about its prominence within Internet, but also points out how the role of distinct actors changes according to material conditions. With this, it expands the reach of multi-stakeholderism, helping to create paths to defend and protect human rights in changing digital contexts.

7. Concluding Remarks: A Framework for Internet Policymaking

Cosmopolitanism, following the proposition by Boczkowski & Siles (2014), can serve as a framework to understand the complexities that surround the Internet. It organizes the different forces and elements that constitute a formal communication process; in this case, it provides a map for the Internet, giving a clear view of the principal interactions that take form and the tendencies of many networks integrated by different actors. The statement made by the Global Commission on Internet Governance (2015) shows that, when studying the Internet, it is easy to give some prominence to certain issues over others. Nonetheless, it is imperative to have an inclusive approach to Internet in order to apprehend its multiple peaks.

Internet policymaking can utilize the cosmopolitan framework to attain circumstantial features from the Internet when needed. The process of constructing a policy should be flexible and adaptive (Adam & Kriesi, 2007; Bianco, 2004; Walker et al., 2001); regarding the Internet, it becomes unavoidable to assume an issue-and-context driven optic due to the changing and unstable substance of the medium, being this one of its principal characteristics. Besides, the concerns located within the Internet tend to embody very specific qualities from a vaster conglomerate. Thus, cosmopolitanism addresses the possibility of finding the main elements that constitute a certain matter through an integral sight of four “cardinal points” –i.e. the quadrants explored in this article.

It is essential to observe that this framework ought not to be considered as fully static, despite its organizational intention. Its spirit is to achieve an integral understanding of processes related to media and technology. The Internet permits a change of positions throughout the ‘cardinal points’ thanks to its malleability. For instance, as analysed above, the roles given by the production and consumption spheres are interchangeable (Siles, 2011): despite the fact that there are power structures that concentrate the generation of content, any user is able to generate some as well; obviously, the impetus of the two experiences will not be the same. Furthermore, cosmopolitanism attaches material implications into the discussion, distinguishing the importance of the technological kernel that holds the medium; from a general perspective, any communicative experience is influenced by discourses but also by concrete structures that can determinate an important part of the final outcomes (Putnam, 2015).

Multistakeholderism sets a principle for Internet governance. It tries to articulate the many voices that are moving around the Internet. As philosophy, it functions based on the ideal of comprehension that presupposes. Notwithstanding this purpose, the model lacks a proper form. Hereby, the proposed cosmopolitanism is a suitable path to find a structure for the crucial values addressed by this optic. The present effort has intended to demonstrate the potential of this framework as guideline for Internet policymaking. Evidently, this is only a first step in order to clear a path for more specific procedures.

Human rights are indispensable for achieving a dialogic and democratic experience of the Internet. Internet governance related to them faces important challenges produced by multiple fronts: from menaces of privacy to restrictions imposed by authoritarian governments, concrete actions are to be done for the defence and promotion of human dignity. Cosmopolitanism, as an ideology and as a framework, helps to elucidate all the edges that cross a certain human rights issue. This proposal can deliver a source of more effective and concrete policies that intends the consolidation of Human Rights on the Internet.

Notas

1. I would like to thank Minna Aslama Horowitz, Ignacio Siles and Johan Espinoza for their insightful comments made during the different writing stages of this paper.

2. The complete universal norms of being, considered by UNESCO (2013, p. 4), are: Human Rights-based and free; Open; Accessible to All; and Multi-stakeholder Participation. The four norms are summarized by the mnemonic ROAM (Rights-based, Open, Accessible, Multi-stakeholder driven).

3. The work of Norris & Inglehart (2009) proposes that the actual global communication system is cosmopolitan due to its reach and eminent presence nearly everywhere. Also, the authors suggest that there are forms of resistance or ‘miscegenation’ in developing or periphery countries that reply and negotiate a hegemonic model of content. Nevertheless, this argument has been highly analyzed and revisited in Latin America since the 1980’s, mostly by García Canclini (1990) and Martín-Barbero (1987).

References

Adam, S. & Kriesi, H. (2007). The network approach. En P. A. Sabatier (Ed.), Theories of policy process (pp. 129-154). Massachusetts: Westview Press.

Ampuja, M. (2011). Globalization theory, media-centrism and neoliberalism: a critique of recent intellectual trends. Critical sociology, 38(2), 281-301.

Bauman, Z., Bigo, D., Esteves, P., Guild, E., Jabri, V., Lyon, D. & Walker, R. (2014). After Snowden: rethinking the impact of surveillance. International political sociology, 8, 121-144.

Beck, U. (2000). The cosmopolitan perspective: sociology of the second age of modernity. The british journal of sociology, 51(1), 79-105.

Beck, U. (2002). The cosmopolitan society and its enemies. Theory, culture & society, 19(1-2), 17-44.

Beck, U. (2009). Critical theory of world risk society: a cosmopolitan vision. Constellations, 16(1), 3-22.

Bianco, J. (2004). Processes of policy making and theories of public policy: relating power, policy and professional knowledge in literacy agendas. Montreal: University of Melbourne.

Boczkowski, P. & Siles, I. (2014). Steps toward cosmopolitanism in the study of media technologies: integrating scholarship on production, consumption, materiality, and content. En T. Gillespie, P. J., Boczkowski, & K. A. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies: essays on communication, materiality and society. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Braman, S. (2004). Where has media policy gone? Defining the field in the twenty-first century. Communication law and policy, 9(2), 153-182.

Castells, M. (2008). The new public sphere: global civil society, communication networks, and global governance. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 78-93.

De Smet, A., Dirix, J., Diependaele, L. & Sterckx, S. (2015). Globalization and responsibility for human rights. Journal of human rights, 14(3), 419-438.

Drake, W. (2004). Reframing Internet governance discourse: fifteen baseline propositions. Internet governance: toward a grand collaboration. Recuperado de http://www.un-ngls.org/orf/pdf/drake.pdf

Dutton, B. (2005). A new framework for taking forward the Internet governance debate. En Position paper for the struggle over Internet governance: searching for common ground forum (pp. 7-10). Oxford: University of Oxford. Recuperado de https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/archive/downloads/collaboration/specialevents/20050505_governance_position_papers.pdf

Dutton, B. & Peltu, M. (2007). The emerging Internet governance mosaic: connecting the pieces. Information polity, 12(1), 63-81.

Echeberría, R. (2012). Human rights and Internet. En W. Kleinwächter (Ed.), Human rights and Internet governance (pp. 50-51). Berlín: Internet & society collaboratory.

García Canclini, N. (1990). Culturas híbridas: estrategias para entrar y salir de la modernidad. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

García Canclini, N. (2012). Communication and human rights. En A. Vega Montiel (Ed.), Communication and human rights (pp. 17-28). México, DF: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Giddens, A. (1986). The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Global Commission on Internet Governance. (2015). Toward a social compact for digital privacy and security statement. Recuperado de https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/toward-social-compact-digital-privacy-and-security

Hall, P. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and State: the case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative politics, 25(3), 275-296.

Hamelink, C. (2011). Global justice and global media: the long way ahead. En S. Jansen, J. Pooley & L. Taub-Pervizpour (Eds.), Media and social justice. Nueva York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hamelink, C. (2012). Internet governance and humans rights: the challenges ahead. En W. Kleinwächter (Ed.), Human rights and Internet governance (pp. 56-59). Berlín: Internet & Society Collaboratory.

Hänska-Hay, M. & Roxanna Shapour, R. (2013). Who's reporting the protests? Converging practices of citizen journalists and two BBC world service newsrooms, from Iran’s election protests to the Arab uprisings. Journalism studies, 14(1), 29-49.

Hintz, A. & Milan, S. (2009). At the margins of Internet governance: grassroots tech groups and communication policy. International journal of media & cultural politics, 5(1-2), 23-38.

Horner, L. (2011). A human rights approach to the mobile internet: Melville: Association for Progressive Communications.

Ingram, H., Schneider A. & DeLeon, P. (2007). Social construction and policy design. En P. Sabatier (Ed.), Theories of policy process (pp. 129-154). Massachusetts: Westview Press.

Kovacs, A. & Hawtin, D. (2013). Cyber security, cyber surveillance and online human rights. Recuperado de https://www.gp-digital.org/wp-content/uploads/pubs/Cyber-Security-Cyber-Surveillance-and-Online-Human-Rights-Kovacs-Hawtin.pdf

Krummer, M. (2005). The struggle over Internet governance: searching for common ground. En Position paper for the struggle over Internet governance: searching for common ground forum (pp. 25-28). Oxford: University of Oxford. Recuperado de https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/archive/downloads/collaboration/specialevents/20050505_governance_position_papers.pdf

Kurbalija, J. & MacLean, D. (2007). Internet governance (draft for discussion). Manitoba: International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Recuperado de https://www.iisd.org/pdf/2008/igsd_common_agenda_bg.pdf

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social. Nueva York: Oxford University Press.

Law, J. (2009). Actor network theory and material semiotics. En B. Turner (Ed.), The new blackwell companion to social theory (pp. 141-158). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Lim, Y. & Sexton, S. (2011). Internet as a human right: a practical legal framework to address the unique nature of the medium and to promote development. Washington Journal of Technology & Arts, 7, 295.

Lucchi, N. (2014). Internet content governance and human rights. Vanderbilt journal of entertainment & technology law, 16(4), 809-856.

MacLean, D. (2005). Governing the Internet as medium and message, model and metaphor. En Position paper for the struggle over Internet governance: searching for common ground forum (pp. 29-33). Oxford: University of Oxford. Recuperado de https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/archive/downloads/collaboration/specialevents/20050505_governance_position_papers.pdf

Martín-Barbero, J. (1987). De los medios a las mediaciones: comunicación, cultura y hegemonía. Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili.

Martín-Barbero, J. (2012). Strategic challenges: information societies and human rights. En A. Vega Montiel (Ed.), Communication and human rights (pp. 157-166). México, DF: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Marx, L. (1997). Technology: the emergence of a hazardous concept. Social research, 64(3), 965-988.

Mayer-Schönberger, V. & Ziewitz, M. (2007). Jefferson rebuffed: the United States and the future of Internet governance. The Columbia Science and technology law review, 8, 188-228.

Morley, D. (1992). Television, audiences and cultural studies. Nueva York: Routledge.

Norris, P. & Inglehart, R. (2009). Cosmopolitan communications cultural diversity in a globalized world. Nueva York: Cambridge University Press.

Osman, F. (2002). Public policy making: theories and their implications in developing countries. Asian affairs, 24(3), 37-52.

Puddephatt, A. (2011). Mapping digital media: freedom of expression rights in the digital age. Londres: Open Society Foundations.

Putnam, L. (2015). Unpacking the dialectic: alternative views on the discourse–materiality relationship. Journal of management studies, 52(5), 706-716.

Raboy, M. (2004). The WSIS as a political space in global media governance. Continuum: journal of media & cultural studies, 18(3), 345-359.

Raboy, M. & Padovani, C. (2010). Mapping global media policy: concepts, frameworks, methods. Communication, culture & critique, 3(2), 150-169.

Schneider, S. & Foot, K. (2004). The web as an object of study. New media & society, 6(1), 114-122.

Siles, I. (2011). From online filter to web format: articulating materiality and meaning in the early history of blogs. Social studies of science, 41(5), 737-758.

Siles, I. (2013). Inventing Twitter: an iterative approach to new media development. International journal of communication, 7, 2105-2127.

Sterne, J. (2006). The mp3 as cultural artifact. New media & society, 8(5), 825-842.

Sterne, J. (2014a). “What do we want?” “Materiality!” “When do we want it?” “Now!”. En T. Gillespie, P. Boczkowski & K. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies: essays on communication, materiality and society (pp. 119-128). Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Sterne, J. (2014b). MP3: the meaning of a format. Londres: Duke University Press.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO (2013). Internet Universality: A means towards building knowledge societies and the post-2015 sustainable development agenda. Recuperado de http://www10.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/2013/12814.pdf

Vallejo, N. & Hauselmann, P. (2004). Governance and multi-stakeholder processes. Manitoba: International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Recuperado de https://www.iisd.org/pdf/2004/sci_governance.pdf

Vedel, T. (2005). The struggle over Internet governance: searching for common ground. En Position paper for the struggle over Internet governance: searching for common ground forum (pp. 63-67). Oxford: University of Oxford. Recuperado de https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/archive/downloads/collaboration/specialevents/20050505_governance_position_papers.pdf

Walker, W., Rahman, S. & Cave, J. (2001). Adaptive policies, policy analysis and policymaking. European journal of operational research, 128, 282-289.

Waz, J. & Weiser, P. (2013). Internet governance: The role of multistakeholder organizations. Journal of telecommunications and high technology law, 10(2), 331-348.

Weber, R. (2009). Internet of things–need for a new legal environment? Computer law & security review, 25(6), 522-527.

Webster, J. & Ksiazek, T. (2012). The dynamics of audience fragmentation: public attention in an age of digital media. Journal of communication, 62(1), 39-56.

Webster, J. (2014). The marketplace of attention: how audiences take shape in a digital age. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ziccardi, G. (2013). Resistance, liberation technology and human rights in the digital age. Netherlands: Springer. Recuperado de https://cryptome.org/2013/03/hacking-digital-dissidence.pdf