Note: Adapted from Scolari et al. (2012, pp. 79-89).

Transmedia storytelling and construction of fictional worlds: aliados series as case study

Tomás Atarama-Rojas

tomas.atarama@udep.pe

Universidad de Piura (Perú)

Recibido: 7 de mayo de 2019

Aceptado: 30 de mayo de 2019

Publicado: 24 de junio de 2019

Para citar este artículo

Atarama-Rojas, T. (2019). Narrativas transmedia y la construcción de mundos ficcionales: La serie Aliados como caso de estudio. Correspondencias & Análisis, (9). https://doi.org/10.24265/cian.2019.n9.02

Abstract

This paper explores the contributions of transmedia storytelling in the construction

of fictional worlds, in an attempt to detect the narrative elements that strengthen the bond of

the audience with the fictional world. The study shows that based on the solid construction

of the poetics of a story, transmedia storytelling can enrich the engagement with a large

audience. To prove this, we analyze the narrative elements and the transmedia strategies

of the series Aliados, produced by Cris Morena Group and broadcasted in Latin America

and countries in Europe.

Keyword: Transmedia storytelling, Fictional worlds, Screenwriting, Fiction, TV series, Aliados.

Resumen

Esta investigación explora las contribuciones de las narrativas transmedia en la

construcción de mundos ficcionales, con el objetivo de detectar los elementos narrativos que

fortalecen la vinculación de la audiencia con el mundo ficcional. Los resultados muestran

que, basados en una sólida construcción de la historia, la narrativa transmedia puede

enriquecer la vinculación con una amplia audiencia. Para probar esto, en la investigación se

analiza los elementos narrativos y las estrategias transmedia de la serie Aliados, producida

por el Grupo Cris Morena (Argentina) y distribuida en Latinoamérica y Europa.

Palabras clave: Narrativa transmedia, Mundos ficcionales, Guión, Ficción, Series de televisión, Aliados.

1. Introduction

Screenwriters have the task of creating fictional worlds capable of engaging the public

to live experiences that generate a deep emotional bond. In this scenario, transmedia

storytelling invites screenwriters to create narratives capable of engaging audiences across

stories that are extended and expanded throughout disparate media and platforms.

What narrative elements strengthen the bond of the audience with the fictional world

in a transmedia story? This question is answered throughout this paper with the help of

Argentinean TV series Aliados (2013-2014) as case study. The series was created and

produced by Cris Morena Group and broadcasted by Telefe in Argentina and Fox in the

rest of Latin America.

Aliados was presented as a successful transmedia experience that has sparked a popular

phenomenon around the world. From the analysis of the series and the products created

to feed the audience experience (via two mobile applications, a print magazine, a photo

album, a live musical, website, CDs, DVDs with special versions, social media accounts,

and more), we seek to detect which narrative elements stand to strengthen the bond of the

audience with the fictional world.

2. Theoretical framework

Transmedia storytelling is one of the most attractive objects of research in the era of

convergence. Indeed, academic interest strengthened with the article “Transmedia

storytelling” by Henry Jenkins in 2003 (Scolari, Jiménez & Guerrero, 2012; Formoso,

Martínez & Sanjuán-Pérez, 2016). As Jenkins (2003) writes: “We have entered an era of

media convergence that makes the flow of content across multiple media channels almost

inevitable”. Or, in Scolari’s words: “Now narratives and media are converging, and we can

no longer analyze them in isolation from each other” (Scolari, 2013a, p. 47). So, it becomes

necessary to approximate screenwriting to transmedia storytelling, because in the current

media ecology the stories told follow transmedia strategies.

Moreover, the audience is changing the way it consumes stories. Specifically, “the

combination of social networks, second screens and TV has given rise to a new relationship

between viewers and their televisions, and the traditional roles in the communication

Wparadigm have been altered irrevocably. Social television has spawned the social

audience” (Quintas-Froufe & González-Neira, 2014, p. 83).

The present research departs from the narratological perspective and will focus on the

contributions of transmedia storytelling in the creation of fictional worlds. Generally,

stories must be understood as transmedia products, which implies a narrative universe

enriched across multiple media. “Almost any beloved fictional world exists in multiple

forms, from multiple adaptations implemented across time to the inordinate amount of

fan-produced works and now marketing campaigns that expand a fictional world” (Dena, 2009, p. 322). The transmedia phenomenon is not an incidental result of the creation of

fictional worlds, but reflects the condition of the narrative itself in an era in which users

“consume” and “prosume” content on an integrated multimodal and multimedia level. To

think fictional worlds today, screenwriters must know transmedia storytelling.

They also should understand their work in terms of world-creation and develop rich

environments, which could support a variety of different characters. “For most of human

history, it would be taken for granted that a great story would take many different forms,

enshrined in stain glass windows or tapestries, told through printed words or sung by bards

and poets, or enacted by traveling performers” (Jenkins, 2003).

The study employs three key concepts: “fictional world”, “possible world” and “transmedial

world”. They refer to the art of creating through narrative elements other realities with

particular rules. However, each concept emphasizes different levels of creation. A “fictional

world”, used by e.g., Dena (2009), Scolari (2014) and Jenkins (2006), depends directly on

the narrative content. Many stories can be told in a unique fictional world, but there is

always a proto-world that explains the settings and characters that act in it.

A “possible world” refers to the total poetic possibilities of the story. In this case, the stories

that can be told are based on the principles of verisimilitude and necessity proposed in

Aristotle’s Poetics (García-Noblejas, 2004). Under these concepts, the audience “configures

a possible development of the events or a possible state of things [...] foretells hypothesis

about world’s structure” (Eco, 1993, p. 160).

The third key concept, “transmedial world”, relates to a world that is an “abstract content

system (…) from which a repertoire of fictional stories and characters can be actualized or

derived across a variety of media forms” (Klastrup & Tosca, 2014). Transmedial worlds consist

of a “textual network” (Scolari, 2014, p. 2403). “A transmedial world is more than a specific

story, although its properties are usually communicated through storytelling [...] Transmedia

storytelling therefore can be seen as a social narrative practice while transmedial worlds are

a social text-based interpretative construction situated at a cognitive level” (Scolari, 2014, p.

2384). The transmedial world implies all the stories that happened or are told in the fictional

world, so this concept includes user-generated content, where the audience (fandom) creates

several complementary stories that can fill the narrative gaps of the principal, or official story.

In this sense, “the concept of transmedia world is proposed as the logical evolution of the

idea of narrative world” (Scolari, Jiménez & Guerrero, 2012, p. 138), because any transmedia

storytelling experience supposes the creation of a transmedial world.

Transmedia storytelling has, according with Guerrero-Pico & Scolari (2016), key elements

to define it, one of those is the expansion of the narrative, that it can be managed by the

producers or writers (top-down), and also managed by the users (bottom-up), where they

create content and share it in social media platforms like YouTube, Twitter, Facebook,

blogs, wikis or fan fiction files. That is what we best known as user-generated content. Both

varieties can be used as strategies of expansion, though the bottom-up complements the

top-down transmedia narrative as it helps to expand its transmedia world.

For this study, we will use possible world as an abstract concept for the creation of the poetic

elements (plot, character, spectacle, argument, theme and music) and the possibilities of

dramatic creation. We will use fictional world when we refer to the creation of one narrative, and

transmedial world when we want to express the world created in relation to different narrations

and media. Thus, fictional world refers to story, while transmedial world emphasizes discourse.

“While the story - or ›histoire‹ - concentrates on what happens, the ›discours‹ focuses on the

way of telling the story. Which narrator figures does the text present? From which perspective

is it told? In which order are the events of the story presented? Which description modes are

used? When speaking about transmedial phenomena, the ›discours‹ level implies more than one

media device” (Zimmermann, 2015, p. 24).

The transmedia phenomenon is not new. Respective terminology was introduced in 2003

by Jenkins and since then the potential of transmedia storytelling has multiplied with new

technologies (Robledo, Atarama-Rojas & Palomino, 2017). Today, transmedia storytelling

in entertainment and fiction is fundamental. Jenkins (2006) emphasized that “a transmedia

story unfolds across multiple media platforms, with each new text making a distinctive

and valuable contribution to the whole” (pp. 95-96), and this contribution represents an

augmentation of the fictional world created by the writers.

A transmedia experience improves the construction of fictional worlds. As Jenkins (2006) notes,

“reading across the media sustains a depth of experience that motivates more consumption.

Redundancy burns up fan interest and causes franchises to fail. Offering new levels of insight

and experience refreshes the franchise and sustains consumer loyalty” (p. 96).

At this point, we need to introduce transmedia extensions. In the transmedia system, we have

a principal text and extensions that expand the story to other touchpoints with the audience.

This concept differs from intertextuality, which according to Scolari (2013b), is a connection of

different parts that are related with each other; extensions, however, not only relate directly to

the central story, but also expand the universe in which it develops. For example, an extension

could be an extra video on YouTube or a webisode on the official website. Key to extensions

is that they generate a connection with the audience. In this sense, “the extension may add a

greater sense of realism to the fiction as a whole” (Jenkins, 2007), because it can join the real

world of the audience. Thus, a fictional world approaches the real world of each fan.

Through extensions, the audience can interact with the fictional world, getting immersed in the

story and filling in the gaps actively (playing, using apps and social networks, and generating

content). As result the audience can feel a stronger narrative pleasure. “Narrative pleasure can

be generally described in terms of immersion in a fictional world [...] Narrative immersion is

an engagement of the imagination in the construction and contemplation of a story world that

relies on purely mental activity” (Ryan, 2009, pp. 53-54). Therefore, transmedia storytelling

can be used as a strategy that can increase the engagement with the fan community.

Fans can build a stronger connection with the fictional world of the story if extensions offer

new levels of development of the story and interesting extra information. “In the ideal form

of transmedia storytelling, each medium does what it does best - so that a story might be

introduced in a film, expanded through television, novels, and comics, and its world might

be explored and experienced through gameplay. Each franchise entry needs to be selfcontained enough to enable autonomous consumption” (Jenkins, 2003). And a central idea

is that screenwriters could explore more creative possibilities if they knew the potentials of

the story and each media to connect emotionally with the fan.

Emotional connection depends on many factors; one being the kind of narrative. A genre

that best facilitates transmedia storytelling strategies is series. “Fiction series are an

attractive genre for these phenomena [transmedia storytelling], because the serial structure

allows designing transmedia strategies that disseminate the content through other media, at

different time points to the issuance of the chapter” (Tur-Viñes & Rodríguez, 2014, p. 116).

Starting with the fiction series, screenwriters can expand the fictional world to other media,

exploring the specific nature of each media. Because “transmedia storytelling represents

a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple

delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment

experience. Ideally, each medium makes its own unique contribution to the unfolding of

the story” (Jenkins, 2007).

Critical in transmedia storytelling is the experience that is not generated only by the story,

but is closely linked to the process of interactivity that is generated from how, where, and

when the story is consumed, and even how audience action feeds. In this sense, we can say

that well- built transmedia stories should perform an exercise in communication strategy in

which the timing and environment (platforms) conjugate.

When screenwriters create the story considering transmedia storytelling, they have to

develop a fictional world that can expand different characters and plots. “Most often,

transmedia stories are based not on individual characters or specific plots but rather complex

fictional worlds which can sustain multiple interrelated characters and their stories. This

process of world-building encourages an encyclopedic impulse in both readers and writers.

We [the readers] are drawn to master what can be known about a world which always

expands beyond our grasp” (Jenkins, 2007). So, transmedia storytelling enriches the

narrative ability to create emotions in public. In Ryan’s (2009, p. 56) words: “Narrative has

a unique power to generate emotions directed toward others. Aristotle paid tribute to this

ability when he described the effect of tragedy as purification (catharsis)”. “This is a very

different pleasure than we associate with the closure found in most classically constructed

narratives, where we expect to leave the theatre knowing everything that is required to

make sense of a particular story” (Jenkins, 2007). The prosumer needs to feel that she or

he can know more and still unexplored areas of the story exist to which they can relate.

This desire to know more about the fictional worlds and the wish of filling in narrative gaps

encourages user-generated content, a whole dimension of transmedia storytelling. Scolari,

following Jenkins, explains that “transmedia storytelling integrates two dimensions: a)

the construction of an official narrative that gets dispersed across multiple media and

platforms (the canon), and b) the active participation of users in this expansive process

(the fandom)” (Scolari, 2014, p. 2384). Transmedia storytelling takes the user involvement

to a new level, because they not only watch the stories, but participate interactively and

intervene, i.e., create new content that expands the universe of the main story (usergenerated content) (Atarama-Rojas, Castañeda-Purizaga & Frías-Oliva, 2017). In fact,

“due to new technological options, interactivity and user participation are parts of many

modern transmedial projects” (Zimmermann, 2015, p. 32).

There is a wide variety of user-generated content, which expands the diegetic universe

of the series and generates a positive response from users who often share and display

content generated by fans, rather than the official content of the series. This gives us

some perspective about the potential of considering the user as a strategic partner in the

production of fiction; giving space within official channels can promote user participation

in today's media ecology. In this sense, Jenkins explains that user-generated content is but

one fundamental element of transmedia storytelling (Jenkins, 2006), and Fernández (2014)

recalls the growing role of the user as a principal agent in the definition of the narrative

universe in the transmedia era.

Likewise, “these external fan practices may be participatory but they are clearly located in

an extradiegetic orbit of the narrative world. This means that these fan activities have little

effect on the narrative” (Ganzert, 2015, p. 40). We support the claim that user-generated

content expands the fictional world, but these practices could only be considered as a

transmedia storytelling strategy when producers encourage fans to generate more content.

So, the narrative gaps “allowed some viewers to evolve from their assumed passiveness in

the general audience to instead become part of the fast-growing fan base” (Ganzert, 2015,

p. 34). Narrative gaps, thus, can increase the audience’s desire to know more. Subsequently,

the audience can start filling in narrative blanks. “These nanotexts bridge the gaps (ellipsis)

in the sequence of events of the TV show” (Scolari, 2013a, p. 58).

Transmedia narrative “also includes texts that make a narrative compression, for example

video recaps, photo-recaps, clips, vids shipping, mobisodes, trailers” (Scolari et al., 2012,

p. 86). “If we consider that many recaps are produced by users, and in some cases they

open new doors to the fictional world or introduce new textual components that expand

our interpretation of the story, then they should be included in our analysis of transmedia

storytelling” (Scolari, 2013a, p. 62).

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Materials

Approaching the goal of the investigation we take as a case study the series Aliados from

Argentina. Aliados broadcasted in 18 countries, including Israel and parts of Europe. The

first season comprised 23 episodes for television and 126 webisodes, while season two

comprised 17 episodes and 88 webisodes. Webisodes and the episodes followed the same

narrative, but there are differences in the length and the time each one was broadcasted.

Thus, the webisodes (between 6 and 10 minutes) were always broadcasted before the episode

(between 45 and 55 minutes). Each episode gathered five or six webisodes. Exclusive

content featured in webisodes as music development, and in episodes as resolution of the

plot.

The series covers social problems such as promiscuity, unwanted pregnancies, bullying,

suicide, anorexia, juvenile delinquency, child labor, alcoholism and domestic violence. It

explores a fictional world in which humans need the help of light beings (angel-like). The

plot establishes that in the last decades, the human race has advanced greatly and rapidly

in science and technology, which is why people have distanced themselves from each other

to the point of forgetting who they are and why they exist. Because of this oblivion, in late

2012 the human race began a 105-day countdown that will either lead to destruction or

revival. The Earth’s future depends on six youngsters: Noah, Azul, Maia, Manuel, Franco

and Valentín. With the help of The Female Energy Creator, they will be assisted by seven

light beings: Ian, Venecia, Inti, Ámbar, Luz, Devi and Gopal. They come from different

parts of the universe with the goal of becoming the “Allies” [Aliados in Spanish] of these

humans and help them in the mission of saving the “human project”.

The series used many strategies of media convergence in distributing elements of its fictional

world through multiple media and platforms. Aliados has been presented as a successful

transmedia experience which caused a fan phenomenon throughout Latin America. The

first episode broadcasted achieved general rating average of 16.3 points in Argentina,

which placed it as the third most-watched TV show of the day. In the rest of Latin America,

Fox reached first place for pay TV channels with Aliados (Marie, 2013). Also, one of

the soundtrack CDs reached Gold status two weeks after launch and four months later

achieved platinum status in Argentina (Sony Music, 2013). The official YouTube channel

attracted over 46 million views.

The following products are analyzed to answer the research questions:

3.2. Methods

Considering the characteristics of the object of study and its novelty in the Latin

American market, this investigation aims to have an exploratory nature to detect the

narrative elements that strengthen the bond between the audience and the possible world

created. In this sense, we analyze all the touchpoints by posing three exploratory research

sub-questions:

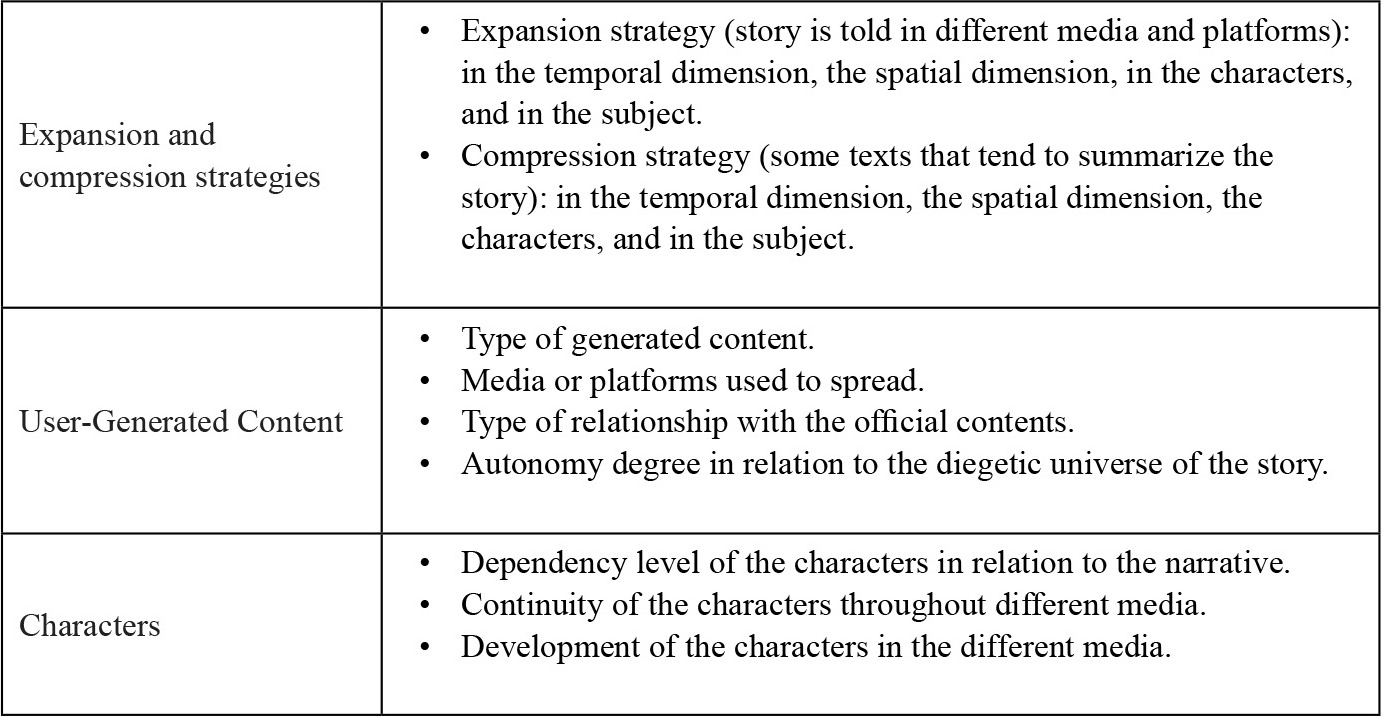

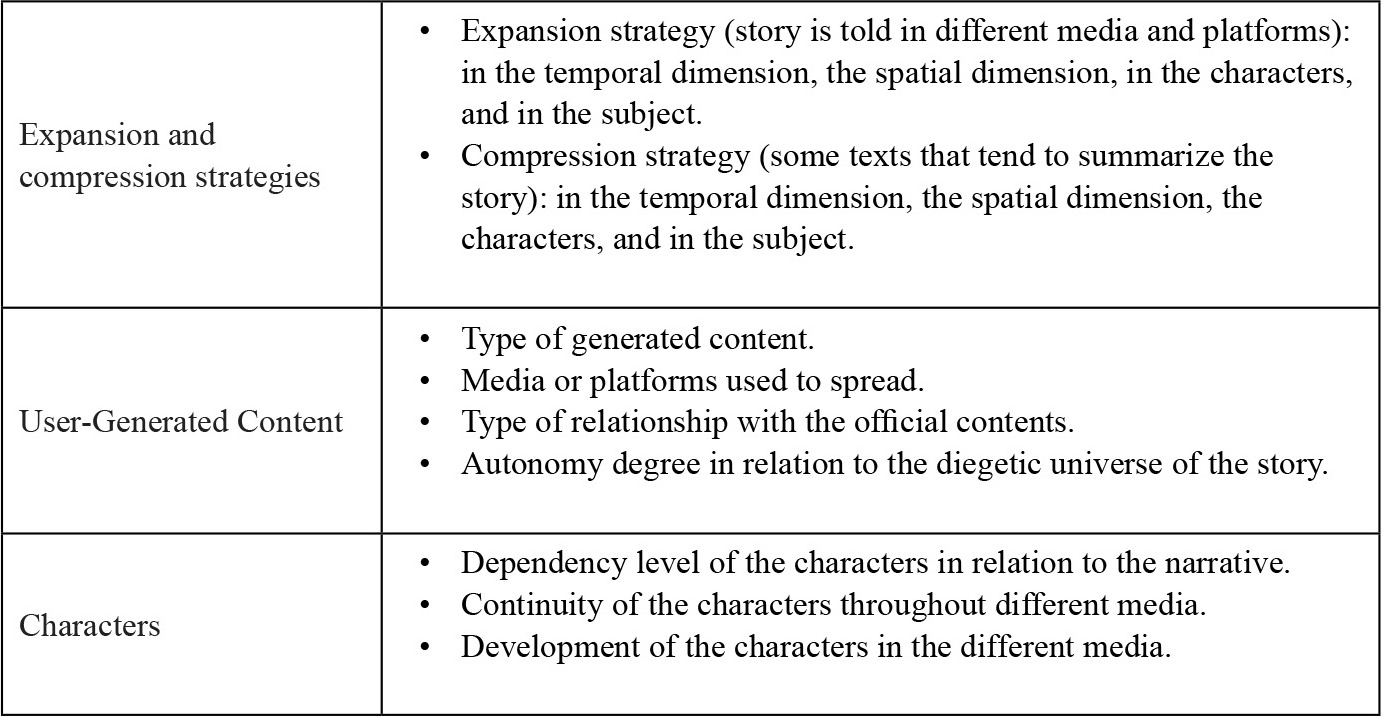

About the process of expansion and compression1

of transmedia storytelling: Was the

diegetic universe expanded via different media and platforms, exploring new corners of

the possible world, or did it present compression processes in which aspects of the diegetic

universe were deleted?

About user-generated content and their connection to the diegetic universe: Was usergenerated content integrated into the transmedia strategy of this series to contribute to the

expansion of the story, or did it relate to it without reaching a syncretic interaction that was

a part of the diegetic universe expansion?

About the independence acquired by the characters in different narratives: Did the characters

take a condition of independence from the series2, so they could interact with users outside

their diegetic universe? Did the characters participate in social networks trespassing the

narrative laws of the diegetic universe designed?

After the first approach, a data-analysis was applied to all the material to determine

the narrative elements that strengthen the bond of the audience with the fictional

world. The analysis sheet served mainly to organize and prioritize the information

that was gathered through the exploratory questions. Then the data-analysis is presented.

Tabla 1: Summary sheet for the content analysis of the transmedia storytelling of Aliados

Note: Adapted from Scolari et al. (2012, pp. 79-89).

The methods not only study each story of the different media, but also the relation between stories and all media and platforms. We apply these methods because “an analysis must therefore consist not only of an accurate closer look on the ›discours‹ of the individual texts but also of an examination of the interdependency of the texts as a whole. This certainly belongs to the ›discours‹ of a transmedially told text” (Zimmermann, 2015, p. 24). Thus, our approach is based on qualitative, not quantitative, indicators.

4. Research findings

The main medium (source) was the narrative content of the story that spread through the

episodes and webisodes (as they contain almost all the material that would later be gathered

in an episode). The original story, the characters and plots, raised in this environment, and

from here other products can expand or compress the narrative. Thus, episodes and webisodes

configure the main narrative world of Aliados, because the protoworld is the story of the

series, and this story is told in episodes and webisodes.

Most material not pertaining to either episodes or webisodes expands the diegetic

universe of Aliados. Among all products, the musical aspect stands out, because the

main characters play, sing, and perform choreographed dances in the main medium, and

this is taken by extension to generate unity and connections between the transmedial

worlds. Indeed, the most-viewed video on the official Aliados channel is the music video

of the song “Refundación” (3 662 047 views until June 2018). This item does not strictly

correspond to the narrative structure, but engages the audience most profoundly with

the music and with the whole world of Aliados For example, in the comments section,

fans express their joy over the video and ask for new content related to the Aliados

phenomenon. Each song developed a story about the life of a character and her or his

subplot. For example, the song “Yo soy Venecia”, which reveals more information about

the Venecia character’s objectives.

Also, the two Aliados books expand the universe as they develop in more detail the characters’

internal conflicts. This touchpoint explores deeply the theme of the story. On the other hand,

the printed magazine, the photo album and the two mobile applications emphasize the

characters as narrative elements easily recognizable in the world of Aliados.

The transmedia extensions of Aliados, even when they expand the limits of the diegetic

universe, use compression strategies. For example, we see characters being eliminated in the

musical, like Ian who did not appear in the show. Although the musical explores a new subplot

about the search of the book of wisdom of Aliados, it relinquishes elements of the main

narrative such as secondary characters or subplots. This implies that the distinction between

expansion and compression is blurry, as the universe can be expanded using compression

tools, and be compressed appealing to extension tools. For example, the musical presented

in Buenos Aires expands the fictional world because it tells stories with new subplots, but in

turn, summarizes other aspects of the main story with simple quotes or directly eliminates

characters of the main story. Ultimately, all actual transmedia contents extend the possible

world, and the concept of compression is a way to expand the fictional world.

The spin-off Aislados represents an expansive practice. This series presents a kidnapping

that happened after the diegetic time of the main text (time-based transmedia strategy).

Additionally, the story plays out in an abandoned house, so we can consider it as the result of

a space-based transmedia strategy, too. This miniseries came at the request of the audience

(they tweeted about it until Cris Morena announced gave in), so we can say it is an example

of fan/audience-based transmedia strategy.

The user-generated content found about Aliados was diverse, there was music videos,

extended trailers, made up trailers, recaps, videos telling the love story of two characters,

unofficial social media, covers of the songs, memes, fan fictions, fan theories (speculations

trying to explain something, or trying to explain what could happen next). The main media

or platforms used to spread this content was social media, such as Facebook, Twitter and

YouTube, and also some blogs for the fan fictions.

Likewise, the user-generated content has not direct relationship with the official content, i.e.,

it doesn’t have intervention in the main narrative or straight connection that affects the main

story, however, it does help to expand the story told in the main source. The most watched

user-generated videos are music videos, suggesting that the music was a key source to spawn

user-generated content.

Much of the user-generated content refers to the trajectory of the producer of the series, Cris

Morena. The contents recalled her previous projects and linked the possible world of Aliados

to a possible wider world, which in turn would be the fiction produced by Cris Morena Group,

whose TV productions are popular in Latin America and parts of Europe (Pis & García, 2014).

The expansive media maintained relative independence with respect to the main narrative.

For example, in Radio Aliada, some characters appeared like real persons, i.e., they appeared

like actors, but keeping within the theme of the main narrative. Although the same theme is

present in all the touchpoints, the narrative conflict the characters must overcome varies with

the media. In this sense, the characters gained some autonomy from the base story, yet failed

to perform autonomously as an element of interaction with the audience on social media and

did not talk and respond to comments.

5. Conclusion

From the above, it can be concluded that Aliados reinforces the experience of its audience

by applying transmedia strategies.

The results show that the biggest emotional bond with the audience grows from the

music: CDs, videos, musical performances and tours. Fans recognize the characters and

experience an extension, not just an adaptation, of the main story by attending musicals and

tours. On social media fans talked about the new subplot, new versions of the songs, and

the performance of characters in the musical. The music carried emotional content because

it represented the theme and the internal conflicts of the characters; the narrative content

linked to the music expanded the possibilities of fans to enjoy each song more.

Two media were essential in the construction of the transmedia fictional world: the official

YouTube channel and the official website. Both platforms allowed users to watch the

webisodes, chapters and musical videos repeatedly and at the same time share this content

on social media.

The social networks, however, only repeated the content, without adding special interaction

with fans, although the series had an official social media presence on Twitter and Facebook.

Thus, social media management did not realize the full potential of these media to compel

the fans.

User-generated content is key in this case, because it helps to expand the fictional world,

even though it is not part of the narrative strategies of the Cris Morena Group.

More importantly, from an induction process with the experience of Aliados, the distinction

between compressive and expansive content can be called into question, because even

contents void of basic elements of the main narrative expand the possible world beyond

initial borders of the original narrative. Otherwise, we would not be dealing with a real

transmedia phenomenon, where each media contributes and enriches the narrative.

Aliados shows that transmedia storytelling can contribute to enrich a fictional world, because

with elements like plot, characters, theme and music of the possible world spreading through

other media and platforms and redirect the story, the audience can increase engagement with

the fictional world. In this case, characters and music had a strong presence in the episodes

and webisodes, so from these elements the other touchpoints increased the engagement

with the audience. In conclusion, the key for transmedia storytelling for a fictional world

is the storytelling itself. In Aliados, the creation and development of the characters and

the linking of music to conflicts of the characters were key for the construction of the

fictional world. Character creation as much as the positioning of music are strategies of

screenwriting.

Latin American artists are just beginning to explore the possibilities of transmedia

productions. “We need a new model for co-creation rather than adaptation-of content that

crosses media” (Jenkins, 2003). Given this unexplored terrain, academic research can

promote a critical and analytical view of these processes to design guidelines that can help

consolidate transmedia strategies in accordance with the requirements of our reality, and so

contribute to train future transmedia creators.

NOTAS

1. Scolari explains that when talking about transmedia storytelling, academics refer to “the expansion of a narrative world through different media and platform. However, are all transmedia experiences ‘expansive’? Are there any

experiences of ‘narrative compression’? Many audiovisual contents, rather than expanding the story, reduce it to

a minimum expression, like in trailers and recapitulations” (Scolari, 2013a, p. 48). We understood compression as

reduction of the narrative content.

2. Independence of the character from the series means that the character can follow a particular path in other media and platforms. For example, if the protagonist can speak in different ways on social media or “Radio Aliada”, we

can affirm that the characters are independent from the series, where they have to speak in a specific way.

References

Atarama-Rojas, T., Castañeda-Purizaga, L. & Frías-Oliva, L. (2017). Marketing

Transmedia: análisis del ecosistema narrativo de la campaña publicitaria “Leyes

de la Amistad” de Pilsen Callao. adComunica, 14, 75-96. doi: 10.6035/2174-0992.2017.14.5

Dena, C. (2009). Transmedia practice: theorizing the practice of expressing a fictional

world across distinct media and environments (unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

Fernández, C. (2014). Prácticas transmedia en la era del consumidor: hacia una definición

del contenido generado por el usuario. Cuadernos de información y comunicación,

19, 53-67. doi: 10.5209/rev_CIYC.2014.v19.43903

Formoso, M., Martínez, S. & Sanjuán-Pérez, A. (2016). La ficción nacional y los nuevos

modelos narrativos en la autopromoción de Atresmedia. Icono14, 14(1), 211-232.

doi: 10.7195/ri14.v14i1.910

Ganzert, A. (2015). We welcome you to your Heroes community. Remember, everything

is connected. A case study in transmedia storytelling. Image, 21, 34-49.

García-Noblejas, J. (2004). Personal identity and dystopian film worlds. Communication & Society, XVII(2), 173-87. Retrieved from https://www.unav.edu/publicaciones/revistas/index.php/communication-and-society/article/view/36329

Genette, G. (1989). Palimpsestos. La literatura en segundo grado. Madrid: Taurus.

Guerrero-Pico, M. & Scolari, C. (2016). Transmedia storytelling and user-generated content:

a case study on crossovers. Cuadernos.info, 38, 183-200. doi: 10.7764/cdi.38.760

Jenkins, H. (2003, January 15). Transmedia storytelling: moving characters from books

to films to video games can make them stronger and more compelling. Retrieved

from http://goo.gl/TU7rWy

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture. Where old and new media collide. New York:

New York University Press.

Jenkins, H. (2007, March 21). Transmedia Storytelling 101 [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/T0ksLe

Klastrup, L. & Tosca, S. (2014, November 18). Transmedial Worlds – Rethinking

Cyberworld Design. Paper presented at the 2004 International Conference on

Cyberworlds. doi: 10.1109/CW.2004.67

Marie, J. (2013, July 23). ‘Aliados’ positions Fox in first place in pay-tv. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/sMAJrd

Morena, C. (Producer). (2013). Aliados [Television Series]. Buenos Aires: Telefe.

Pis, E. & García, F. (2014). Development of the audiovisual market in Argentina: an

export industry. Palabra clave, 17(4), 1137-1167. doi: 10.5294/pacla.2014.17.4.7

Quintas-Froufe, N. & González-Neira, A. (2014). Active audiences: social audience

participation in television. Comunicar, 23(43), 83-90. doi: 10.3916/C43-2014-08

Robledo, K., Atarama-Rojas, T. & Palomino, H. (2017). De la comunicación multimedia

a la comunicación transmedia: una revisión teórica sobre las actuales narrativas

periodísticas. Estudios sobre el mensaje periodístico, 23(1), 223-240. doi: 10.5209/ESMP.55593

Ryan, M. (2009). From narrative games to playable stories. Toward a poetics of

interactive narrative. StoryWorlds: a journal of narrative studies, 1, 43-59. doi: 10.1353/stw.0.0003

Scolari, C. (2013a). Lostology: Transmedia storytelling and expansion/ compression

strategies. Semiotica, 195, 45-68. doi: 10.1515/sem-2013-0038

Scolari, C. (2013b). Narrativas transmedia. Cuando todos los medios cuentan. Barcelona: Deusto.

Scolari, C. (2014). Don Quixote of La Mancha: transmedia storytelling in the grey zone.

International journal of communication, 8, 2382-2405.

Scolari, C., Fernández, S., Garín, M., Guerrero, M., Jiménez, M., Martos, A.,

Obradors, M., Oliva, M., Pérez, O. & Pujadas, E. (2012). Narrativas transmediáticas, convergencia audiovisual y nuevas estrategias de comunicación. Quaderns del CAC, 15(1), 79-89. Retrieved from https://www.cac.cat/sites/default/files/2019-01/Q38_scolari_et_al_ES.pdf

Scolari, C., Jiménez, M. & Guerrero, M. (2012). Transmedia storytelling in Spain: four fictions searching for their cross-media destiny. Communication & Society, 25(1), 137-163.

Sony Music (2013, July 25). Aliados disco de oro!! Retrieved from https://goo.gl/skuJcQ

Tur-Viñes, V. & Rodríguez, R. (2014). Transmedia, fiction series and social networks. The case of Pulseras Rojas in the official facebook group (Antena 3. Spain). Cuadernos.info, 34, 115-131. doi: http://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.34.549

Zimmermann, A. (2015). Blurring the line between fiction and reality. Functional transmedia storytelling in the german TV series about: Kate. Image, 22, 22-35. Retrieved from http://www.gib.uni-tuebingen.de/own/journal/upload/bb53f351f013a250142bad066e4156b5.pdf